Why did European countries take over of Africa? Was it inevitable? What might have been if they had agreed to establish diplomatic and trading relations with African rulers? What was Africa like then? What glimpses do we have from the first outsider?

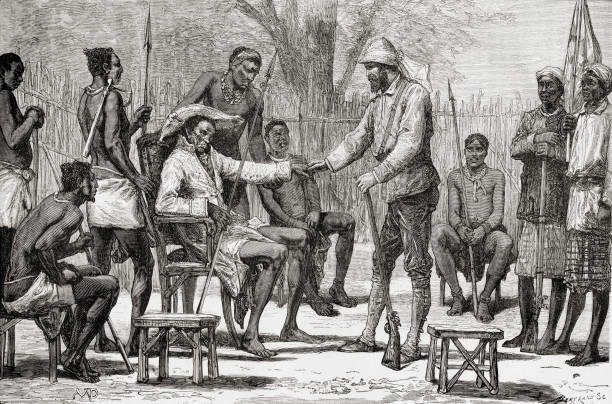

I have just finished reading a little known book by Verney Lovett Cameron, a British naval officer who walked across Africa from Bagamoyo on the coast of Tanzania to Benguela in Angola. It took him four years from the beginning of 1872 to 1875 and he nearly died – several times. His aim was to find the sources of the Congo river and discover which streams he crossed might lead him to it. But in this he failed and was forced to head to the west coast which he finally reaches sick and exhausted. Today Cameron comes across as an honest, determined but unimaginative man who carried all the racial attitudes of the time but is deeply sympathetic to African societies which are being destroyed by slavers who create roaming gangs of displaced people who rape, rob and kill to survive. As Cameron and his train of carriers and guards make their way across the continent they become weaker and more and more dependent on the very people Cameron was determined to expose: the slave traders, Arab and African.

Two shocking facts – new to me – and a question emerged from the book. In Europe’s schools today we are taught that Britain “abolished the Atlantic slave trade” in 1807. In fact it continued. Portugal agreed to stop taking Africans to America in 1836 but did not enforce it. Nor did the United States and Britain. So Portuguese ships continued to take slaves from southern and central Africa to Brazil and the southern Caribbean across the southern Atlantic until the 20th century. Brazil was ruled by Portugal until 1822 but it did not abolish slavery until 1888. In east, central and southern Africa millions of Africans were seized and force marched as slaves to Zanzibar to work on plantations there or sent north to “Arabia”. My question is why aren’t Saudi Arabia, Yemen and the Gulf not – like Brazil – populated by the descendants of black Africans?

Cameron eventually reached the fortified villages of Portuguese traders in what is now Angola and from there made his way to Benguela and took a boat back to Britain. In his book he proclaims the wealth of Africa – vegetable and mineral. He lists sugar cane, cotton, oil palm, coffee, tobacco, seseme, timber, nutmeg, pepper, rice, wheat, rubber, hemp, beeswax, cattle hides, wool, salt and cinnabar as well as gold, silver, iron, coal, copper and other minerals. He even finds a village that is sitting on a rich vein of gold but the people who live there have no use for it.

What Cameron comes across again and again are Africans who have been attacked and captured as slaves and the remainder, mainly women and old men, forced from their homes. They in turn starve or attack other villages out of desperation. By the beginning of the 20th century Africa was severely depopulated. It is still relatively empty so there should be no complaints about Africa’s growing numbers. The population of the continent has doubled since 1990 and will reach 2.4 billion by 2050. This is a challenge for their governments but should be seen as something positive, not negative.

This is a crucial time. A new generation is pushing through. Whatever personal or political decisions are taken now by the peoples of Africa, African presidents, the United Nations, Chinese, Indian and western businesses, western aid donors and the multitude of actors in Africa today they will hugely affect the future of Africa and the planet for decades to come. The good news is that this new generation is able to talk about it to each other, continent-wide and world wide. The consensus seems to be coalescing around social issues and technology not politics directly. Meanwhile the homunculi presidents who squat in their fortress palaces are obsessed with their wealth, power and status. But they are – as ever – fearful of these continent-wide and global internet discussions. Jacob Zuma, Robert Mugabe, Eduardo dos Santos all made attempts to create dynasties but all have failed. That would not have happened 10 years ago. Museveni – elected 30 years ago – is a good example. He still grips desperately to power, too frightened to let go. Increasingly greedy and dictatorial he tried to put his wife and then his son in power. He crushes anyone who might replace him. He has become the very thing that he once fought against. What would a conversation between the old and the young Museveni sound like now?

The moment will come when these viral debates coalesce into movements with clear objectives and programmes of disruption to topple the owner-rulers. This movement has already begun.